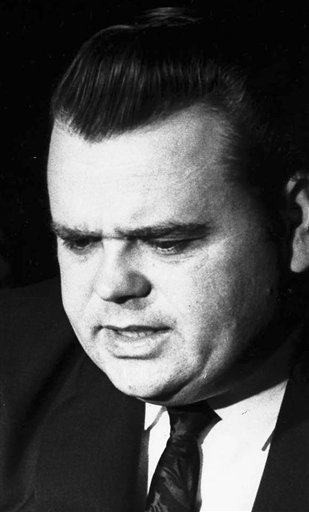

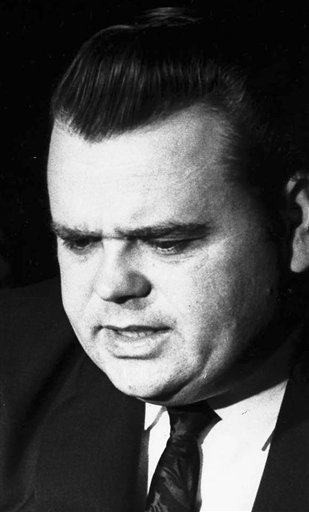

Rev. Billy James Hargis personally attacked an author during a 15-minute “Christian Crusades” segment broadcast by a Pennsylvania broadcasting station. The Court ruled that the station had to grant response time under the FCC fairness doctrine. The policy attempts to ensure that broadcast stations’ coverage of controversial issues. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

A policy of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the fairness doctrine attempted to ensure that broadcast stations’ coverage of controversial issues was balanced and fair. However, many journalists opposed the policy as a violation of the First Amendment rights of free speech and press.

The fairness doctrine took effect shortly after the creation of the Federal Radio Commission (FRC) in 1927 and was continued by its successor, the FCC, until the late 1980s. In its 1929 Great Lakes Broadcasting Co. decision, the FRC asserted that the “public interest requires ample play for the free and fair competition of opposing views, and the Commission believes that the principle applies to all discussions of issues of importance to the public.”

During this period, licensees were obliged not only to cover fairly the views of others, but also to refrain from expressing their own views. The fairness doctrine grew out of the belief that the limited number of broadcast frequencies available compelled the government to ensure that broadcasters did not use their stations simply as advocates of a single perspective.

In its 1940 Mayflower Broadcasting Corp. decision, the FCC abandoned the restriction on expressing personal views, and the modern fairness doctrine was born.

In the ensuing decade, the FCC laid out a twofold duty for broadcasters under the fairness doctrine. First, broadcasters were required to cover adequately controversial issues of public importance. Second, such coverage must be fair by accurately reflecting opposing views, and it must afford a reasonable opportunity for discussing contrasting points of view.

The commission later obligated stations to actively seek out issues of importance to their communities and air programming that addressed those issues.

The fairness doctrine gained greater legitimacy from the 1969 Supreme Court decision in Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. Federal Communications Commission. In that decision, the Court ruled that a Pennsylvania broadcasting station was required to grant airtime for a response to an author who had been personally attacked by Rev. Billy James Hargis during a 15-minute “Christian Crusades” segment broadcast by the station.

The FCC later promulgated rules dealing with stations’ obligations after they broadcast personal attacks, including those made during political editorializing. In 1971 the commission began requiring stations to report efforts to address issues of concern to the community.

Reporters argued that they, not the FCC, should make decisions about balancing the fairness of stories. They believed that the fairness doctrine had a chilling effect by deterring them from tackling controversial issues rather than worrying about whether they could meet the FCC’s fairness standards.

By the 1980s, the fairness doctrine was losing clout. The deregulatory nature of the Reagan administration and the technological advances that were rendering scarcity arguments moot combined to pressure the FCC to abandon the doctrine. In 1987 the FCC formally abolished it.

The doctrine, however, continues to have its defenders (Arbuckle 2017).

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated in 2017. Audrey Perry is a First Amendment, election, and campaign finance law attorney. She has served as counsel to several presidential campaigns. Ms. Perry is of counsel at the Sacramento law firm Bell, McAndrews & Hiltachk and an adjunct professor at Brigham Young University Law School, where she teaches Election Law.