Addition to Reserve: A parcel of land that is added to the existing land base of a First Nation or is used to create a new reserve. The legal title to the land is set apart for the use and benefit of the First Nation making the application. Footnote 1

Buckshee agreements: Agreements for use of land by third parties that do not fall under the legal provisions of the Indian Act .

Capital moneys: Indian Moneys derived from the sale of surrendered lands, non-renewable resources and the capital assets of a band.

Certificate of Occupation: A document certifying that an individual member of a First Nation has been given a temporary allotment (lawful possession in the form of the right to temporarily use and occupy a parcel of reserve land).

Certificate of Possession: A document certifying that an individual member of a First Nation has been given an allotment (lawful possession in the form of the right to use and occupy a parcel of reserve land) by the Band Council, which is then approved by the Minister. Legal title to the land remains with the Crown. Footnote 2

Customary Allotments: Customary Allotments are instruments issued by a Band Council to an individual or are based on informal agreements between band members. They are not registered in the Indian Land Registry and are not legally enforceable arrangements.

Deeds System: A land registry system that registers transactions on title rather than conferring title. Footnote 3 The Indian Land Registry is similar to a deeds system as it registers transactions, although all title belongs to the Crown.

Delegated Authority and 53/60: Status conferred upon First Nations under the Reserve Land and Environmental Management Program and the previous Reserve Land Administration Program. Delegated authority and 53/60 status give First Nations increased responsibilities to administer land transactions under the Indian Act . Footnote 4

First Nations Land Management Regime: An alternative to the Indian Act land management regime that provides certain First Nations with powers to manage their reserve land and resources under their own land codes. Once in effect, certain sections of the Indian Act dealing with land, resources and environment no longer apply to these First Nations. Footnote 5

Indian Land Registry: A database maintained by Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) that consists of documents related to interests in reserve (and any surrendered) lands that are administered under the Indian Act . Footnote 6

Land Designation: A vote by a First Nation community and subsequent approval by the Minister to allow for a surrender of land that is not absolute. This allows for leasing to non-band members on a specific parcel of land. Footnote 7

Land Survey: The division, measurement and mapping of a parcel of land, resulting in a legal description that clarifies land tenure and can be referred to when issuing interests in land. In the context of Administration of Reserve Land , surveys as carried out under the authority of the Minister of Natural Resources Canada upon request by AANDC . Footnote 8

Locatee Lease: A lease of lands held by a member of a band who is in lawful possession of the land.

Revenue moneys: Indian moneys derived from a variety of sources, which include, but are not limited to, proceeds from the sale of renewable resources, reserve land instruments (leases, permits, etc.), fines and interest earned on band capital and revenue moneys held in the Consolidated Revenue Fund.

Section 35 Easement: The grant or transfer of less than a full interest in reserve land to an expropriating authority for a specific purpose, where the underlying interest remains with Canada under reserve status. Footnote 9 For example, provinces may be granted Section 35 easements to allow for hydro transmission lines.

Self-Governing Land Management Regime: The system for granting interests in self-governed First Nation reserve lands. Similarly to the Indian Act and First Nations Land Management Act regimes, the Department maintains a registry to record these interests.

Torrens System: A land registry system that confers title to the land and guarantees priority of title in addition to registering instruments stemming from that title. Footnote 10 This is the system typically used by provincial governments in Canada.

Treaty Land Entitlement: In this context, an Addition to Reserve being processed as a result of the settlement of a treaty. These Additions to Reserves are done in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba specifically, and fall under unique legislation allowing them to be approved via Ministerial Order rather than Order in Council. Footnote 11

In accordance with the Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation requirement to evaluate program spending every five years, the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) has conducted an evaluation of the Administration of Reserve Land Sub-program (sub-program 3.2.3 of the Department's Community Development Program).

The sub-program carries out AANDC 's statutory responsibilities as it relates to land management under the Indian Act . Specifically, the sub-program consists of four core activities: Additions to Reserve, by which First Nations can create or expand land bases; creation, registration, renewal and monitoring of rights and interests in reserve land, in which AANDC administers land transactions on-reserves; land surveying and clarification of title, in which AANDC works with Natural Resources Canada to clarify internal and external reserve boundaries to facilitate Additions to Reserves and land transactions; and management of oil and gas activity on-reserve, in which the special operating agency Indian Oil and Gas Canada manages legal interests related to oil and gas on reserves. The program also involves some administrative duties related to collection of Band Moneys. Aside from $750 000 in Grants and Contributions for land survey funding administered by the National Aboriginal Land Managers' Association, all of the program spending is operational spending.

The evaluation was conducted by EPMRB with the assistance of the consulting firm Prairie Research Associates, which assisted in the development of the methodology, interviews, data review, case studies and the final report. Evaluation findings were informed through literature review, document review, key informant interviews and a review of program data. Four case studies were conducted of the Regional Support Centres created in 2012, with an additional case study conducted focusing on Indian Oil and Gas Canada.

Key findings from the evaluation are as follows:

The federal government has clear statutory responsibility for land management and oil and gas activity on reserves stemming from the Indian Act and the Indian Oil and Gas Act .

Key informant interviews and discussions with communities during case studies indicate that there is a continued need for all elements of the Administration of Reserve Land program beyond simply their statutory nature. Together, the program activities represent the core elements of land management required for First Nations to benefit from reserve land and key informants note that regional staff provide valuable assistance to low-capacity First Nations with these activities. Stakeholders' opinions were divided on the relevance of the Indian Land Registry in its particular format, but there is consensus that cleaning up the data and implementing formal policy or regulations would enhance its credibility.

While there is an ongoing need for the program's management of the Indian Act land management regime, key informants, case studies and literature review also all suggest that providing alternative land management options, such as the First Nations Land Management Act, best responds to a variety of ongoing needs among First Nations.

Document review indicates that Administration of Reserve Land is aligned with government priorities. Specifically, the Government has signaled through the Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development that one of its priorities is to continually improve the administration of reserve land.

Key informants and a review of departmental performance reports indicate that the program has undertaken significant work during the evaluation period to improve its design and delivery in response to the Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development as well as previous evaluations, audits and Parliamentary reports. However, there are also opportunities to improve program performance across its business lines:

Key informants noted that it is important to update the Land Management Manual, which serves as a guide to Lands Officers' work with legal instruments in the regions. This is advisable first to improve the performance value for First Nations by ensuring that guidelines on legal instruments are conducive to flexible approaches for economic development; and second, to ensure that guidelines meet the standards of current jurisprudence, given that the manual has not been updated since 2002-2003.

The analysis of efficiency and economy focused on the impact of program restructuring in 2012, which saw the creation of the Regional Support Centres and the transfer of registration activities to regional offices:

A review of data on resource allocations indicates that program costs include substantial full time equivalents devoted to Additions to Reserve and permits, leases and other land transactions, and that new registration responsibilities in the regions have also presented a cost in employee time. Evidence demonstrates that opportunities for increasing efficiencies include building First Nations' capacity through the Reserve Land and Environmental Management Program, streamlining the Additions to Reserve process and monitoring regions' registration responsibilities going forward.

Finally, while Indian Oil and Gas Canada has been found to generally operate in an efficient manner, key informants expressed concern around its ability to retain its knowledgeable staff during oil and gas market fluctuations. As such, a strategy for continued recruitment and retention is advisable to mitigate this risk in future.

As a result of these key findings, it is recommended that AANDC :

Project Title: Evaluation of Administration of Reserve Land

Project #: 1570-7/14100

Land is vitally important to the community and economic development aspirations of First Nations. First Nations have significant social, economic and cultural connections to their land. The Lands and Economic Development Sector of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada AANDC) understands the importance of effective land management in promoting the social and economic prosperity of First Nation communities. Activities to improve the administration of reserve land have been identified as key sector priorities and work has been ongoing to strengthen and improve land administration policies, procedures and processes.

As noted in the evaluation, significant progress and improvements have been made on a range of land administration activities. These improvements are the result of the strong partnerships between AANDC headquarters and regional staff, First Nations, non-governmental organizations and other government departments. These partnerships and relationships will continue to support ongoing improvements.

The evaluation findings will inform future planning, process and policy improvements, and as appropriate will be used as input in corporate planning ( i.e. , Report on Plans and Priorities) and other performance monitoring and reporting activities. The evaluation findings will inform future policy and process improvements.

Most of the issues identified in the evaluation report are not new and in fact have been the focus of concerted improvement efforts over the last two years. The Lands and Economic Development Sector has taken specific, measurable, attainable, relevant and time - bound actions to address many of the issues identified in the evaluation report. Ongoing collaboration with key stakeholders and partners such as the Association of Canada Lands Survey, the National Aboriginal Land Managers Association, Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), and First Nations will continue and will lead to tangible improvements in land administration policies, systems and tools.

More work will be done to improve land administration for First Nations. Improvements are necessary to ensure the continued success and prosperity of First Nation communities and economic development initiatives.

2015 -2016 fiscal year

The Lands and Economic Development Sector (LEDS) has made investments in land use planning through the land use planning pilot initiative. To increase collaboration and efforts to facilitate community planning related to land use:

The Lands and Environmental Management Branch has engaged the Association of Canada Lands Surveyors, the National Aboriginal Land Managers Association, and NRCan to explore efficient ways to improve land surveys. To date, the following actions have been taken to address some of the issues raised in this report:

A comprehensive plan to modernize the Land Management Manual is currently under development. This plan will be used to update the Land Management Manual so as to provide clear, consistent, and current guidelines to regional staff and land managers.

The Lands and Environmental Management Branch, in partnership with the National Aboriginal Land Managers Association, will provide training to AANDC staff and First Nations on land administration policies and processes ( i.e. , Lands 101, Designation, and Leasing).

The Lands and Environmental Management Branch has taken the following actions to enhance efficiency and effectiveness of the Indian Land Registry and related IT systems:

2015-2016 fiscal year

The Lands and Environmental Management Branch has taken the following measures to enhance efficiency and effectiveness of the Regional Support Centres:

The Lands and Environmental Management Branch will take actions to address issues raised in this report by:

I recommend this Management Response and Action Plan for approval by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee

Original signed by:

Michel Burrowes

Director, Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch

I approve the above Management Response and Action Plan

Original signed by:

Sheilagh Murphy

Assistant Deputy Minister, Lands and Economic Development

Administration of Reserve Land is part of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada's (AANDC) Land and Economy programming, identified as a sub-program of the Community Development Program as per AANDC 's 2014-15 Program Activity Architecture.

The program carries out AANDC 's statutory responsibilities as it relates to land management under the Indian Act. It includes four key activity areas:

Almost all of the program funds for these activities are identified as Operational and Maintenance Funds.

In accordance with the 2009 Treasury Board Secretariat's Policy on Evaluation to evaluate program spending every five years, the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) of AANDC has conducted an evaluation of the federal Administration of Reserve Land .

The overall purpose of the evaluation is to provide reliable evaluation evidence that will be used to support policy and program improvement and, where required, expenditure management, decision making and public reporting.

The evaluation of the Administration of Reserve Land addresses the Policy on Evaluation's Core Issues of relevance and performance (including cost-effectiveness and cost-efficiency). Additionally, the evaluation considers issues related to the program's design and delivery and considers best practices and lessons learned.

The period under evaluation is fiscal year 2009-10 to fiscal year 2013-14 but was guided by the Performance Measurement Strategy for the program.

Terms of Reference for the evaluation were approved in June 2015 by AANDC 's Evaluation Performance Measurement and Review Committee. The evaluation was undertaken by EPMRB between June 2014 and September 2015 with the assistance of a consulting firm, Prairie Research Associates Inc.

This section of the report includes a brief description of the Administration of Reserve Land sub-program, including its activities, expected outcomes, management structure, and resources associated with the sub-program. Footnote 12 This section also presents the linkages between the Administration of Reserve Land sub-program and the Community Development program area under which Administration of Reserve Land is currently situated in the Department's Program Alignment Architecture.

Generally, the Administration of Reserve Land sub-program is in place to ensure that reserve land held in trust by the Crown for First Nations is managed based on the requirements outlined in the Indian Act . This may include: adding land to a reserve for First Nations' use; preparing, reviewing and processing legal documents related to land use; conducting land surveys to make sure boundaries are correctly outlined; providing expertise on oil and gas development; and maintaining financial trusts on behalf of First Nations for the money that comes from the use of the land.

More specifically, the Administration of Reserve Land sub-program comprises four core business lines:

In addition to these core business lines, Administration of Reserve Land includes some activities related to the management of Band Moneys, the subset of Indian Moneys that are for the communal use of the band. Section 62 of the Indian Act distinguishes two categories of Indian Moneys: capital and revenue. Land management officers in regional offices will ensure revenue from leases, permits and other legal instruments are deposited into the Consolidated Revenue Fund and held in trust under the name of the First Nation. Funds are then managed and distributed by the Indian Moneys, Estates and Treaty Annuities Directorate of the Resolution and Individual Affairs sector of the Department. This is done in accordance with the Manual for the Administration of Band Moneys.

All activities undertaken as part of the federal Administration of Reserve Land sub-program are implemented within the legislative framework provided by the Indian Act and, as such, they only apply to First Nations whose land and economic development activities are governed by this legislation.

A Performance Measurement Strategy for Administration of Reserve Land was approved in March 20, 2014, by the AANDC Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee.

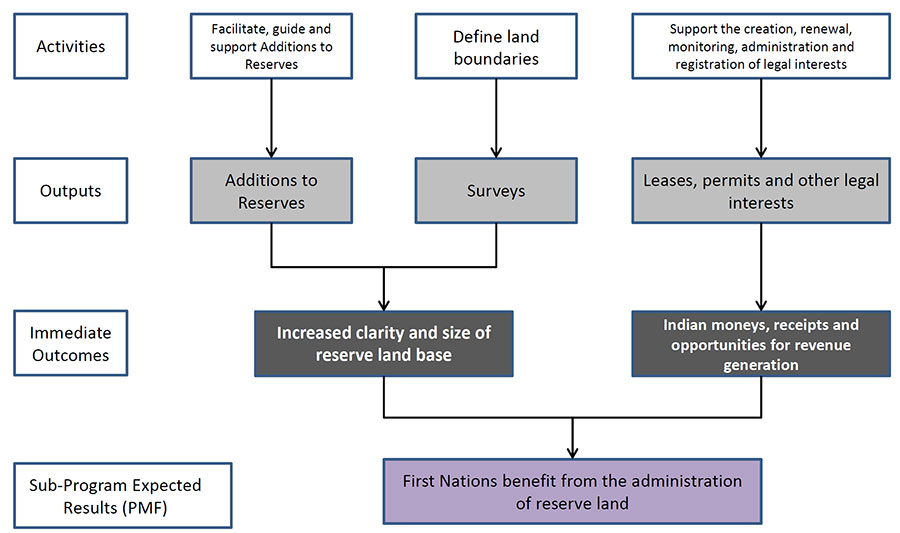

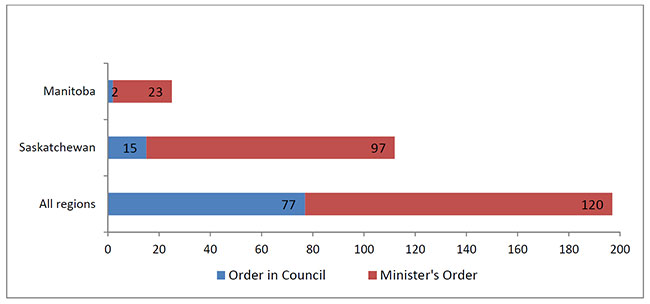

The logic model of the Administration of Reserve Land sub-program is outlined in the figure below:

Activities involving supporting the Additions to Reserve process, defining land boundaries and supporting the creation, renewal, monitoring, administration and registration of legal interest results in the following immediate outcomes for the sub-program:

The expected results of the Administration of Reserve Land are:

Further, this sub-program is expected to contribute to the Community Development Program's expected results, which are:

In order to demonstrate performance, as part of the Performance Measurement Strategy, the program tracks the number of Additions to Reserves and total acres added; the number of new leases, permits and other instruments being registered; the value of money collected by Indian Oil and Gas Canada (IOGC); the value of funds collected from legal instruments; and the number of surveys created. (See Appendix B: Evaluation Matrix for indicators).

AANDC Headquarters and the regional offices both play a direct role in the implementation of activities undertaken through the Administration of Reserve Land . A number of other stakeholders support the implementation of these activities.

The Assistant Deputy Minister, Lands and Economic Development, has overall responsibility for the Administration of Reserve Land sub-program. From an operational perspective, it is administered by the Lands and Environmental Management Branch, Lands and Economic Development Sector, which is responsible for:

Regions support the implementation of the sub-program through the following activities:

Four regional support centres were created in 2012 to assist regions with new program responsibilities involving instrument registration and Additions to Reserves. Generally, they are responsible for maintaining up-to-date templates for regions' use, communicating operational changes to regions, and support to regions in the preparation of their submissions. Each centre is responsible for a specific program function:

Between 2009-10 and 2013-14, AANDC invested a total amount of $130.5 million in Operations and Maintenance funds for the federal Administration of Reserve Land.

Table 1 provides a breakdown by fiscal year:

Source: Chief Financial Officer

The evaluation examined Administration of Reserve Land activities undertaken and outcomes achieved between fiscal year 2009-2010 and fiscal year 2013-2014. This includes program design and delivery changes in 2012, whereby registration of land instruments and some ATR responsibilities were decentralized from Headquarters to the regions and four Regional Support Centres were created to assist regions in their work related to registration of land transactions, designations, and Additions to Reserve.

The evaluation focuses on AANDC commitments as per the program's logic model and examines the relevance, effectiveness, efficiency and economy and design and delivery of program activities, outputs and outcomes.

Terms of Reference were approved by AANDC 's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee in June 2014. Field work was conducted between March and June 2015. The Terms of Reference outline the scope, methodology, key issues and resources for the evaluation.

The evaluation was conducted between June 2014 and September 2015.

It should be noted that Band Moneys, while part of the scope of this evaluation, was not a main focus of this evaluation, given that this component was recently evaluated as part of an evaluation of the Indian Moneys, Estates and Treaty Annuities Footnote 14 , as well as having only partial jurisdiction falling under the Lands and Economic Development Sector.

This evaluation was considered, and further, several key informant interviews were undertaken, in order to consider this aspect in the overall evaluation of Administration of Reserve Lands.

For the purpose of this evaluation, the outcome statements in the logic model of the 2014 Performance Measurement Strategy, and associated indicators, where available, were used to measure performance.

As per the Treasury Board Directive on the Evaluation Function and the approved Terms of Reference and program's logic model, the evaluation issues focussed on the following core evaluation issues and questions were addressed:

1. To what extent has there been a need for providing support and guidance with respect to the Administration of Reserve Land?

2. How responsive has AANDC been to that need?

3. To what extent has the sub-program been consistent with the objectives and priorities of the federal government?

4. To what extent does the sub-program contribute to AANDC 's strategic outcomes and the goals associated under the Community Development program?

Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

(assessment of the role and responsibilities of the federal government in delivering the program)

6. Are the division of roles and responsibilities between AANDC and stakeholders regarding the Administration of Reserve Lands appropriate in order to effectively deliver the program and contribute to supporting the program's expected results?

7. To what extent can the newly revised 3.2.3 Performance Measurement Strategy contribute to performance measurement, management and reporting (e.g., can the strategy support the assessment of results?)

8. Are there opportunities ( i.e. Notable best practices and lessons learned) for altering the design and/or delivery of the program in order to improve its performance?

9. In what ways does the sub-program create the conditions for First Nations to have a land base ready to support economic development? (Ultimate Outcome)

10. To what extent does the sub-program create the conditions for First Nations pursuing greater independence/self-sufficiency and sustainable economic development?

11. To what extent are First Nations benefitting from the Administration of Reserve Land?

12. In what ways has the clarity and size of the reserve land base changed because of the sub-program's activities?

13. To what extent has the sub-program facilitated greater revenue-generating opportunities for involved First Nations?

14. What factors (internal and external) have helped or hindered to achievement of expected results?

15. Have there been any unintended positive or negative impacts around AANDC 's assessment and remediation of contaminated sites on-reserve?

16. To what extent is gender-based analysis relevant in the Administration of Reserve Land?

17. What are the costs to engaging in the following program activity areas (Additions to Reserves, surveys and leases, permits and other legal interests) and related outputs and are there opportunities for increasing program efficiencies?

18. To what extent are AANDC 's activities able to complement- or did they unnecessarily duplicate- related activities undertaken?

19. What best practices or key factors of success can be identified for federal Administration of Reserve Land?

The following recent evaluations and reviews of activities pertaining to the Administration of Reserve Land sub-program were considered in the scoping of this evaluation and to inform the evaluation issues and methodology:

The following reviews also contributed to informing the evaluation:

Subsequent to the approval of the Terms of Reference, a Working Group/Advisory Group was formed. The purpose of the Working Group/Advisory Group was to provide feedback on key pieces of the evaluation, including the methodology, preliminary findings and final report. The Working Group/Advisory Group included members from AANDC program staff both at headquarters and in the regions, as well as a representative from Indian Oil and Gas Canada.

The development of the methodology report was primarily informed by the Performance Measurement Strategy (dated March 2014) and through preliminary consultations with program management during the development of the Terms of Reference. An initial review of program documents was also conducted as part of the process.

The methodology report was subject to an internal peer review focus group for added quality assurance.

Data collection and analysis were conducted between September 2014 and July 2015.

The evaluation's findings and conclusions are based on the analysis and triangulation of the following multiple lines of evidence. (Appendix B, Evaluation Matrix):

A literature review was conducted on land management and economic development on-reserve with a specific focus on the legal and regulatory framework of the Indian Act and its impact on economic development. While international literature was consulted, it was found that there are not many comparable international examples and so primarily domestic literature was drawn upon. Program relevance was examined within this legal and regulatory framework and compared with other land management regimes to understand the unique context in which reserve land operates.

Documents were summarized, analyzed, and findings populated in a literature review summary template. Common themes and insights were interpreted in the summary document and later used for the triangulation of findings with other lines of evidence.

A document and file review was conducted, and included a review of the following:

Data analysis was conducted on data related to each of the key program components to assess program outputs related to effectiveness and efficiency. This included a review of data from the following sources:

Though program data was used as supporting evidence wherever possible, these data sources were particularly useful for assessing evaluation questions regarding design and delivery changes; clarity and size of the reserve land base; revenue-generating opportunities; and costs of program delivery.

To assess performance, the following information was examined: changes in number, type and size of ATR ; volume and type of instrument; amount of royalties; and number of surveys requested/funded. These data were then measured against the program's 2014 Performance Measurement Strategy.

The assessment of efficiency and economy focused on the program changes in 2012 where Headquarters staffing was restructured, registration activities were devolved to the regions and support centres were created to assist regions in their work. Two key questions that emerged from this analysis were whether the 2012 changes were affecting output levels and performance across program business lines and whether resources had been saved resulting from the changes.

As such evaluators examined the change in performance data pre- and post-2012 for major changes and also assessed information collected regarding instrument registration times (separated by permit and non-permit) pre- and post-2012. An internal Lands and Economic Development study of full time equivalent allocation across the regions for 2013-14 was cross-referenced with internal documentation on the planned resource savings related to the 2012 changes to assess whether program activities were now being conducted successfully with fewer resources.

The program does not track efficiency and economy information as part of its Performance Measurement Strategy, therefore the data analysis would allow for an examination of trends only.

A total of 64 key informant interviews were conducted. This included 13 program representatives at Headquarters, 29 regional staff Footnote 15 , nine other AANDC staff, five federal partners, four external experts and four representatives of Aboriginal organizations.

Interview responses were grouped by interview question and then assessed to identify key themes. Key informant themes were grouped in the following categories: the Indian Act and AANDC 's role in land administration; Additions to Reserve; the Indian Land Registry; Land Surveys; Creation of land instruments; and resourcing of support centres, regions and Headquarters. These themes were then used to support the triangulation of findings within the guiding framework of the evaluation issues and questions.

In March of 2015, four case studies were conducted of the regional support centres created during program restructuring in 2012:

Case study interview guides were created that addressed the evaluation questions detailed above. However, the specific focus of the case studies was the efficiency and economy of the support centres and the extent to which they facilitated the program activities of ATR , Designations, Section 35 submissions and registration of legal instruments. Discussions and interviews held during case studies provided valuable first-hand assessment with which to supplement the limited data regarding efficiency and economy of the new program structure.

Case studies included interviews with key support centre and lands staff in the regional offices, or focus groups where feasible. Case studies also included document and data review where applicable. They were supplemented with interviews with staff in other regional offices who engage with the support centres on a daily basis.

A case study of Indian Oil and Gas Canada was conducted in May 2015. Evaluators traveled to the agency headquarters outside of Calgary to interview senior management on program relevance, performance and design and delivery. Tsuu T'ina First Nation, which conducts oil and gas activity, was also visited to obtain a First Nation's perspective on the role of IOGC .

Evaluators also interviewed land managers in several communities travelled to as part of the evaluation of the Lands and Economic Development Services Sub-Program . Interview guides were designed to capture information about both programs and, as such, included questions related to land instruments, Additions to Reserves, registration activities and the usefulness of the Reserve Land and Environmental Management Program (RLEMP) in facilitating land transactions. The following communities were visited:

A number of considerations, including strengths and limitations of the evaluation methodology are noted:

Timing posed some limitations on the extent to which the evaluation could consider fully the evaluation issues and questions. Notably, the regional support centres began operations in December of 2012, mid-way through the period covered by the evaluation. As such, consideration of their performance, efficiency and economy is based on roughly two years of operation and does not span the full five year period under evaluation.

Assessing the relative efficiency of regional responsibilities pre- and post-program restructuring in 2012 was also challenging given that the available data for full time equivalent allocations in the regions was available for the evaluation in estimate form and only for fiscal year 2013-14. As such, the evaluation data analysis is ex-post in nature and can identify potential trends. In order to address this, the evaluation methodology employed multiple lines of evidence to substantiate any shortcomings of data with other lines of evidence, namely through document and literature review and key informant interviews and extensive case study work involving interviews.

The evaluation employed both quantitative and qualitative methods, however, it should be noted that, where the reliance on quantitative data was not possible because it was either unavailable or in a format not conducive for undertaking typical evaluation work, the evaluation relied heavily on key informant interviews and case study work substantiated by information in document and/or literature review. .In such cases, care was taken to ensure that it was made explicit that content is based primarily on interviewee statements.

This evaluation was undertaken concurrently with an evaluation of the Lands and Economic Development Services Sub-Program (3.2.1). As such, evaluators had the opportunity to draw upon evidence from the concurrent evaluation to inform the evaluation of Administration of Reserve Land . Specifically, economic development staff and community case study key informants were asked interview questions related to land management under the Indian Act , land surveys and the Additions to Reserve process. This allowed the evaluation team to integrate additional key perspectives into the evaluation of Administration of Reserve Land .

Prairie Research Associates was contracted by EPMRB to assist in the following components of the evaluation: development of the methodology, including data collection instruments; planning and conducting of case studies; conducting key informant interviews; conducting a program data review; developing preliminary findings; and validating the document and literature reviews. This allowed for additional technical expertise during the evaluation process. As project authority, EPMRB also reviewed and approved all Prairie Research Associates deliverables.

The following internal quality assurance processes were also applied to the evaluation:

The federal government has a specific legislative mandate to manage land transactions and oil and gas activity on-reserves stemming from the Indian Act and the Indian Oil and Gas Act .

There is no statutory requirement to add land to reserves. However, the federal government has authority for reserve lands under the Indian Act , and so once land is transferred by another government department, a province, municipality or third party to be added to reserve following a Ministerial Order or Order in Council, its management falls under the responsibility of the federal government. Furthermore, the Government does have an obligation to add land to reserves when ATR fall under the Legal Obligations category, as ATR s in this category are a result of treaty settlements, specific claim settlement agreements or court decisions. In contrast, under non-Treaty Land Entitlement (TLE) categories, there is no legal obligation to add land to reserves and, as a result, this is typically done in light of other considerations specific to a First Nation.

As properly surveyed lands are required for ATR and land transactions, land surveys are a necessary part of the program. Approving land surveys is a federal responsibilit Footnote 16 : Section 24 of the Canada Lands Surveys Act clarifies that reserve land falls under the responsibility of the Surveyor General of Canada when surveying is required. Section 29 outlines surveying for external boundaries of a reserve (known as official plans) and Section 31 outlines surveying for internal division of land (known as administrative plans). The Surveyor General will issue instructions to a private federally-certified land surveyor to conduct the land surveys.

The land tenure system under the Indian Act differs significantly from other Canadian jurisdictions. On-reserve, title is held by the Crown on behalf of First Nations as per Section 18 of the Indian Act and thus, AANDC has legislative duties to exercise in this area on behalf of the Minister. As such, the Indian Act contains a series of administrative clauses that govern the following types of land transactions, which fall under two broad categories of land holdings: communal holdings (held and administered by the Band) and individual holdings (allocated by Council, with approval by the Minister, to individual band members):

In practice, under this regime, roles and responsibilities of AANDC and First Nations differ depending on the land management status of the First Nation. Under the Indian Act land management regime, AANDC is responsible for creating headleases, permits and other legal instruments on Crown land based on the needs of First Nations.

If First Nations are participating in LEDSP , however, they are expected to draft the legal instruments. These are then submitted to AANDC regional offices for final approval and registration. Under delegated authority or Section 53/60 status (achieved under the former Reserve Land Administration Program ), a First Nation is responsible for the process of creating legal instruments.

However, regional key informants have noted that, in practice, LEDSP First Nations often communicate extensively with regional offices to ensure documents are correctly drafted. The Department of Justice is also routinely consulted in cases where legal clarification is needed.

Registration of instruments

All land transactions falling under the categories outlined directly above are registered in the Indian Land Registry System as per sections 21 and 55 of the Indian Act . Footnote 19 Until December of 2012, all registrations were done at AANDC Headquarters. Currently, however, when a First Nation operating under the Indian Act land management regime completes a transaction, they submit it to the regional office for registration. It should be noted that unlike provincial registries that operate under 'Torrens' systems, the Indian Land Registry more closely resembles a 'Deeds' system. In other words, whereas provincial systems maintain lists of title and serve to confer and clarify that title, under the Indian Act, all title belongs to the Crown. As a result, the Indian Land Registry System does track transactions based on title, but it does not establish priority or certainty as to transactions that may relate to a title (with the exception of assignment of leases on designated lands). Footnote 20

It should be noted that all of this is in contrast to First Nations under FNLM , where the community is solely responsible for creating the legal instrument, which is then registered at Headquarters.

Some First Nations operate under an alternative land management regime known as customary allotments, whereby band councils choose to allocate lands to individuals without formal registration. While the system does not require departmental approval, this approach to land use and occupation is not legally enforceable in a court of law. Footnote 21 Literature reviewed notes that without this legal enforcement, this land cannot be used as collateral, making investment and economic development much more difficult. Footnote 22 It is estimated that 80 percent of individual allotments, 50 percent of overall band leasing and 66 percent of short-term land use on-reserves is done via customary allotment or 'buckshee' agreements with non-band members. Footnote 23

The Indian Oil and Gas Act outlines the federal responsibility for oil and gas activities on-reserve. Specifically, Section 3 gives the Governor in Council the power to issue leases, permits and licenses for the exploration of oil and gas on Indian Lands, as well as power over disposition of interests and prescribing royalties. Section 4 states that royalties are to be held in trust for First Nations, and Section 6 requires the Minister of AANDC to consult with bands that will be affected by oil and gas activities. Key informants noted that the Department has a fiduciary responsibility to manage oil and gas on behalf of First Nations.

Indian Moneys are typically generated from legal instruments under the land management system. Indian Moneys are governed by sections 18 (2), 28 (2), 35 (1), 38 (1), 39, 61-69 and 104 of the Indian Act , with sections 61-69 in particular describing how this money is to be managed. Footnote 24 Particularly relevant to this evaluation are the sections governing Band Moneys, which are the collective moneys to be spent in the benefit of the band: Sections 66 and 69, which authorize expenditure of Revenue accounts, and Section 64, which authorizes expenditure of capital accounts. Capital moneys are derived from the sale of surrendered lands or the sale of the capital assets of a band. These moneys include royalties, bonus payments and other proceeds from the sale of timber, oil, gas, gravel or any other non-renewable resource. Revenue moneys are defined as all Indian moneys other than capital moneys. They are derived from a variety of sources, which include, but are not limited to, interest earned on band capital and revenue moneys, fines, proceeds from the sale of renewable resources ( i.e. , crops), leasing activities ( i.e. , cottages, agricultural purposes, etc.) and rights-of-way. Capital and revenue moneys are held in separate interest-bearing accounts under the name of a particular First Nation. While lands officers ensure money is deposited into capital and revenue accounts, it is generally officers outside of Lands branches who are responsible for approving First Nations' requests for use of funds.

There is a continued need for all elements of the Administration of Reserve Land program; together they represent the core elements required for First Nations to benefit from reserve land: Access to valuable land; clarification of land tenure; legally sound instruments for economic activity (including oil and gas); documenting certainty of instruments; and revenue collection.

The evaluation has found a continued need for the ATR process.

In some cases, this continued need is for purposes of historic redress. Footnote 25 Such ATR s typically fall under the Legal Obligations category of Additions to Reserve. Many of these ATR s are distinct because they fall under specific legislation pertaining to Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba that facilitate the process for ATR s stemming from Treaty Land Entitlement Agreements. In some cases, ATR s under this category also arise as a result of court rulings or specific claim settlement agreements. There is a clear continuing need for the Legal Obligations category of ATR in order to provide land owned by the Crown to First Nations. Case study key informants referred to the duty of the Crown and the importance of reconciliation with First Nations when discussing the need to ensure such ATR s are processed in as timely a manner as possible.

There is also a continued need for ATR s related to economic opportunities as well as community and social needs. The previous evaluation of land management activities noted that between Confederation and 1996, the collective Aboriginal land base shrunk by two thirds; this is in contrast to the growth of the Aboriginal population by 45 percent during the same period. Footnote 26 Consequently, a growing population often requires more residential areas and many First Nations are looking for means to leverage economic opportunity as well. For some First Nations, these economic opportunities may lie outside of the reserve and thus require purchasing new land. In its case study work, the evaluation team witnessed the economic benefits First Nations were able to leverage off of land that had been recently added to reserve.

It was also noted, however, that in some cases, it is more beneficial for First Nations to keep fee-simple land and that this does not prevent them from leveraging its economic benefits.

Surveys provide a necessary support function to other components of the sub-program as they are required for Additions to Reserves, Designations and legal instruments and land transactions (including Certificates of Possession, leases and permits) Footnote 27 .

In addition to being required for legal instruments, Additions to Reserves and Designations, surveys help to delineate where assets exist on-reserves and who has claims to these assets, as well as to define the external boundaries of a reserve, preventing encroachment by third parties. Some literature reviewed for the evaluation stresses the importance of providing certainty over title to property, Footnote 28 and surveys help to fill this need by defining boundaries on-reserves. While some bands may wish to hold their lands communally, others wish to divide them into individual holdings and so for these bands providing a clarity of parcel fabric that matches the off-reserve context can help provide certainty to businesses and other stakeholders.

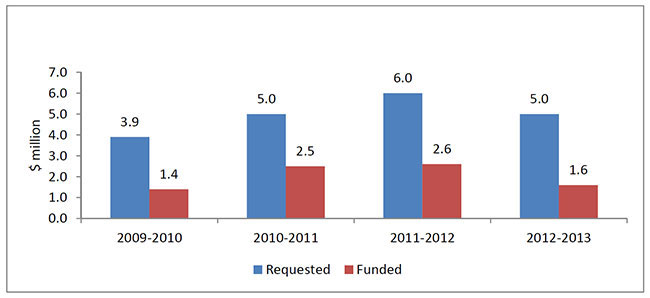

While there is a clear need for the survey function, key informants were divided over the extent to which surveys should be funded by AANDC as opposed to being paid for by bands and individuals: Currently, AANDC only provides funding for surveys that have a communal benefit as opposed to for specific lots. One key informant suggested that the rationale behind this prioritization method stems from the concept that surveys such as those for individual land holdings in residential areas would typically be the responsibility of an individual in any other Canadian jurisdiction, and therefore should not be funded when compared with surveys for communal benefit. Other key informants expressed concerns that without funding for internal surveys, parcel fabric will not be adequately maintained, leading to future disputes and a lack of clarity for the purposes of land administration. In some cases, new survey needs also arise as they are required to define the extent of environmental issues or to correct incomplete or incorrect surveys conducted previously. As is further discussed in Section 4.2, demands currently outstrip supply for land surveys: during the evaluation period, the Department was able to accommodate only 40 percent of survey requests, further indicating an ongoing need for the survey function.

There is a need for AANDC 's involvement in instrument creation to provide legal and administrative support to First Nations, as the Indian Act land regime can be quite complex. As an example, as a precursor to a lease on band land being signed with an outside party, a First Nation must first undertake a Designation whereby the land is surveyed and the community holds a formal vote on the proposed land use; although the Designation process was simplified during the evaluation period (to be discussed in Section 4.1), several key informants and First Nations community representatives noted this process can still take several years, is expensive, and requires significant legal capacity for land descriptions and voting procedures. This is in contrast to the FNLM regime where the complexity of land transactions depends on the land code that each First Nation chooses to adopt.

Several key informants argued that while the Indian Act land management regime may present cumbersome requirements, it also provides the advantage of legal protection to First Nations. As mentioned above, most liability falls on the Crown as the authority behind the instruments. This benefits First Nations that have limited administrative or legal capacity. As such, key informants indicated that a portion of regional offices' work includes maintaining templates for standard documents such as leases and permits to ensure land instruments meet current legal requirements. Alternatively, First Nations would face significantly higher legal fees ensuring the documents were legally sound.

This concept was reinforced by one First Nations land manager who felt their community was better suited to remain under the Department's legal responsibility than to transition to the First Nations Land Management regime. Key informants at Headquarters and in regional offices also noted that, on occasion, AANDC is seen as a neutral third party to assist in land management when there are challenging political divisions within the community.

This legal and administrative support is of need not just to First Nations but to AANDC as well. Given that liability for legal instruments on-reserve falls mostly on the Crown, land administration expertise is important to mitigate the risk of improperly created land instruments and thus increased liability on the part of the Department.

IOGC administers the Indian Oil and Gas Act , under which it manages oil and gas activities for First Nations.The agency undertakes a number of activities in support of First Nations involved in oil and gas development, including the negotiation, issuance and administration of agreements with oil and gas companies; the completion of environmental reviews; the monitoring of oil and gas production and sales prices; the collection of monies such as bonuses, royalties and rents; and the monitoring of legislative and contractual requirements. The agency is staffed with experts in engineering, geology, and legal guidance, which is useful for First Nations communities that do not have the expertise or financial means to acquire guidance in such areas.

Key informants noted that, similarly to the role AANDC plays in creation of other legal instruments, these experts have a central role in providing First Nations with lower capacity the guidance needed to obtain fair agreements for their resources.

While stakeholders' opinions were divided on the value of the Indian Land Registry, there is consensus that cleaning up the data and implementing formal policy or regulations would enhance its credibility.

Section 21 of the Indian Act states that the Department is responsible for maintaining a Reserve Land Register in which to enter details related to "Certificates of Possession, Certificates of Occupation and other transactions respecting lands on-reserve." Section 55 (1) further states that the Department is to maintain a Surrendered and Designated Lands Register, to record details regarding any transaction affecting surrendered or designated lands. Together, these registers are more commonly known as the Indian Land Registry, a system that is thus mandated by law. However, the particulars of the registry are not defined by the Indian Act and the evaluation has found diverging opinions on the value and purpose of the registry in its current form.

In particular, key informants were divided on whether the registry lends legal certainty to instruments in light of the fact that its purpose is not to confer title. Some argue that any legal instrument that is properly designed creates a solid legal foundation. The fact that the federal government is systematically engaged as the title holder also serves to strengthen the legal certainty surrounding such instruments. In that context, the registry serves an important, but distinct purpose by offering a publically available repository of transactions related to surveyed pieces of land. While it may not confer finality over competing claims related to land held by the Crown in cases where two instruments are registered to the same parcel of land, key informants argued it offers critical information that serves multiple purposes for the ongoing planning and management of reserve land.

While recognizing these benefits, others argue that the registry system has the potential to broaden its purpose in order to provide greater economic development opportunities. These stakeholders' views were aligned with the literature that argues that the Indian Act land tenure system suffers from weak property rights that are necessary to facilitate economic development. Footnote 29 Proponents of this argument suggest that a Torrens registry system, which confers title, is more effective than a system whose primary purpose is to track transactions based on pre-existing title. They argue that the certainty that accompanies a Torrens system would strengthen the capacity of First Nations to attract investments in their communities by removing any ambiguity as to the existence and priority of legal instruments related to these pieces of land. As such, they argue that the registry should rest on a legislative or regulatory framework that provides finality as to the existence and priority of legal instruments related to specific pieces of reserve land.

While key informants were generally divided between these two views, relatively common ground was found on practical steps to take to strengthen the value of the registry: first, to clean up inconsistencies in its data, which a number of key informants stated are not currently reliable; second, to put in place formal policy or regulations. The program is currently working on ways to improve the registry function, which will be discussed in Section 4.1.

The 2013 evaluation of Indian Moneys, Estates and Treaty Annuities found that there is an ongoing need for Band Moneys because there is currently no widespread alternative to access these funds, given the requirements prescribed by the Indian Act . Footnote 30 Key informants for this evaluation noted that for some First Nations, this system is preferable over an outside trust as holding accounts with AANDC avoids fees they would have to pay otherwise. If a First Nation does not have enough revenue to make these other fees justifiable, it is preferable to remain with AANDC and as such, there is a continuing need for Band Moneys for some bands.

However, key informants also spoke about the importance of increased autonomy for First Nations, particularly in the area of governance over their moneys. Key informants felt that there is a need to shift toward a model where First Nations have more control over their moneys, such as the First Nations Oil and Gas and Moneys Management Act (FNOGMMA). FNOGMMA is an alternative piece of legislation, enacted on April 1, 2006, that allows First Nations to assume control of their capital and revenue trust moneys held by Canada; currently, there is one First Nation operating under the Moneys Management portion of FNOGMMA . In addition to FNOGMMA , there is a growing alternative Band Moneys design under the Indian Act to be discussed in Section 4.1.

Key informants, case studies and literature review all suggest that providing a variety of land management options, including the Indian Act and the First Nations Land Management Act, best responds to a variety of ongoing needs among First Nations depending on their legal, administrative and economic capacity:

It is important to note that the argument that there is a continuing need for the land tenure system stemming from the Indian Act predominantly comes from key informants and documents review, whereas literature generally advocates either for changes to the current regime or for a move toward greater self-sufficiency under systems such as the First Nations Land Management regime. Footnote 31

Key informants also expressed a range of opinions; for some, there will always be a need for AANDC to support some bands, particularly those with limited land management capacity. Others felt that the Indian Act land management regime is an unsustainable and ineffective system that does not adequately support economic development and constrains First Nations. For these key informants, the Indian Act was only the beginning of a 'continuum' of phases of responsibility, where First Nations could gain increasing land management control through LEDSP , the First Nations Land Management regime and, ultimately, self-government. As such, they felt that more resources should be devoted to transferring land management ability and capacity directly to First Nations as opposed to streamlining Indian Act procedures. The promotion of sectoral self-governance described by these key informants is aligned with findings from the literature that indicate primary efforts should be focused on increasing community control over land management. Footnote 32

According to key informants, the Indian Act and the First Nations Land Management regimes have differing advantages and disadvantages based on their respective regulatory requirements and levels of legal protection offered. A variety of land management tools will best respond to the ongoing need for land management across First Nations in Canada. Therefore, just as there is a continued need for AANDC 's involvement in land administration, there is also a continued need for alternatives to the Indian Act land tenure system.

Multiple sources indicate that the current level of technical land management expertise found in some First Nations is a hindrance to autonomous land management; as such, there is a continued need for capacity-building efforts such as LEDSP , and this need is fundamentally linked to Administration of Reserve Land and the transitionary approach to the First Nations Land Management regime discussed in Section 3.2.7.

In a 2015 survey conducted by National Aboriginal Land Managers' Association in Ontario of 48 land managers, 13 environment officers and 35 economic developments officers, respondents highlighted project management and strategic planning training as an ongoing need; specifically, 78 percent of lands and environment respondents said the most beneficial training they could take would be in land use planning and 62 percent of respondents also identified project management as an area in which they required training. Land managers also identified Geographic Information System technology, surveys and appraisals, and land instruments as the most beneficial and necessary training areas to their work. As two thirds of land managers and economic development officers participating in the survey indicated that there was no training plan in place for their positions, it is likely that there is a lack of skills development in the aforementioned areas. While results of this study cannot be taken as representative of the country or fully definitive in Ontario, the responses to the survey suggest an ongoing need for support in these areas.

Several key informants stressed the importance of AANDC 's capacity-building role in reserve land management. It was suggested that capacity could be built by AANDC through greater funding and resources to assist in hiring land and environmental managers. Key informants indicated that the department's focus should not be on communities that can internally build capacity, but on communities that are unable to build capacity without AANDC 's support. It should be recognized that although capacity building activities are officially a component of LEDSP (3.2.1), they still have an impact on, and are thus relevant to discussion of, 3.2.3.

Administration of Reserve Land is aligned with government priorities. Specifically, the Government has signaled through the Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development that one of its priorities is to modernize land management regimes.

The Administration of Reserve Land sub-program is aligned with government priorities, particularly the 2009 Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development . In particular, the framework calls for enhancing the value of Aboriginal assets, and specifically for a modern lands and resource management regime, speaking to the need for modernizing Indian Act land management practices. Footnote 33 Moreover, the framework establishes that Additions to Reserve "are considered essential to economic progress." Footnote 34 This support is reiterated in the 2011 Canada-First Nations Joint Action Plan and the 2013 Speech from the Throne, in which the Government stated that it would "continue to work in partnership with Aboriginal peoples to create healthy, prosperous, self-sufficient communities." Footnote 35 As such, the program links to the broader government priority in two clear ways: a simple-to-use Additions to Reserve process allows First Nations to create or expand a land base that facilitates economic development; and a modern land management system allows First Nations to more readily create legal instruments through which to leverage economic opportunities. Thus, it is clear that not only is the program aligned with government priorities, but that a stated government priority is in fact to continually improve the program. The extent to which staff have been engaged in improvement during the evaluation period is discussed in Section 4.1.

At the beginning of the evaluation period, in 2009-10, the Report on Plans and Priorities listed completing Treaty Land Entitlement ATR s as a priority. Footnote 36 ATR s continued as a priority during the evaluation period; the 2013-14 Report on Plans and Priorities lists streamlining the ATR process as a priority. Footnote 37 Moving forward, the program is also a priority for AANDC ; the 2014-15 Report on Plans and Priorities states that improving leasing on-reserve through implementation of the new locatee lease policy and guidelines as well as improving the ATR policy and tracking system are priorities. Footnote 38

Furthermore, the 2014-15 Report on Plans and Priorities noted that updating the Indian Oil and Gas Regulations as a means to facilitating oil and gas activities for economic development is a government priority as well. Footnote 39

The Federal Framework , as discussed above, calls for the modernization of the land management regime and also recognizes the importance of Additions to Reserve moving forward. The program has focused both on Additions to Reserve and on the land transactions processes during the period under review.

Regarding Additions to Reserve, the Government and the Assembly of First Nations committed to reforming the ATR policy and process in their 2011 joint action plan. Footnote 40 The Senate report on Additions to Reserve further strengthened this mandate by recommending the program identify policy options for: allowing pre-reserve designations on land to be added to reserve; support mechanisms for First Nations in negotiating with municipalities; best practices to avoid predatory pricing of land; and streamlining procedural requirements for ATR s, as was also identified in a 2009 Report from the Office of the Auditor General. Footnote 41 Similar recommendations either on addressing specific challenges in the process or on revising the federal policy have also come from the Office of the Auditor General (2009), Footnote 42 a 2013 AANDC Audit of the Additions to Reserve process, Footnote 43 a 2010 AANDC evaluation of Contributions for land management Footnote 44 and the 2014 House of Commons report on land management. Footnote 45 The program has since followed up by working with National Aboriginal Land Managers' Association to develop a toolkit for supporting communities through the ATR process; the National Additions to Reserve Tracking System has also been implemented to more easily monitor progress of ATR files. Footnote 46 Furthermore, where a revised policy was recommended AANDC responded by noting it has completed a draft of a new policy anticipated to mitigate some of the issues faced during the ATR process (discussed in Section 4.2.1 of this report). However, it is important to note that this policy has yet to be approved and formally adopted.

The 2013-14 Departmental Performance Report notes that AANDC and Natural Resources Canada worked during the evaluation period to improve survey administration by implementing electronic approvals, removing duplication of survey efforts and ensuring instructions provided to surveyors are clearer; ultimately, the report suggests, these efforts streamline the process so that surveyors can make greater use of the survey season and provide higher quality legal descriptions. Footnote 47

Key informants also indicated that an interdepartmental letter of agreement was signed between AANDC and Natural Resources Canada to clarify the minimum requirements for a survey and therefore to lower the costs of survey products.

The program has also taken steps to improve several types of land transactions. In particular, Section 207 of the Jobs and Growth Act 2012 amended the Indian Act so that a simple majority vote is required to designate land on-reserve, which can save a significant amount of time and money (discussed further in Section 4.4.2). This has been accompanied by a Designations toolkit and training similar to that for ATR s to support communities through what can sometimes be a complicated process.

The program has also been working to simplify policies. For example, during the evaluation period, a new 'locatee lease policy' was developed; one legal expert explained that the policy clarifies that individuals can choose the fees of their leasing as long as they have documents confirming their rights related to the land. Though not why the policy was implemented, this has the added benefit of saving AANDC money as it removes the expensive appraisal step. Furthermore, the policy clarifies that individuals can lease to themselves, which makes mortgaging easier as individuals can demonstrate they have a defined interest in the land.

Key informants noted that one of the most effective actions the program has taken to respond to the commitment of modernizing land management has been to develop templates for legal instruments. A new commercial lease template, for example, has been developed and implemented to simplify commercial leasing activity on-reserve, making land transaction processes quicker and less expensive. Key informants noted, in fact, that having access to these templates not only streamlines the process, but can save First Nations legal fees they would otherwise be paying for the drafting of contracts in an off-reserve context.

The program is currently engaged in updating its oil and gas regime to ensure it continues to be effective and efficient for the First Nations that use it.

Key informants noted that modernizing the Indian Oil and Gas Act , 1974, and its associated regulations is intended to eliminate the existing regulatory gap. Levelling the playing field between off-reserve and on-reserve oil and gas activities will reduce barriers to economic development and will allow the federal government to better fulfill its obligation to manage oil and gas resources on First Nations lands.

The proposed amendments to the Act address the need to manage all aspects of industry operations on First Nation lands. In addition to modernizing dated regulations and providing greater certainty for all stakeholders, the amendments will help to ensure environmental protection of First Nation lands, increase regulatory compliance, and facilitate the collection of royalties and other monetary compensation due.

Although now passed into law, the amended Indian Oil and Gas Act will not come into force until there are new Indian Oil and Gas Regulations . A joint process is currently underway with oil and gas producing First Nations and the Indian Resource Council to develop the new regulations.

Key informant views on how to improve the Indian Land Registry are in line with several reports developed during the evaluation period: In March of 2014, a comprehensive study of land management by the House of Commons recommended modernizing the current land registration process. Footnote 48 Program staff responded by undertaking two studies – one of the information technology platform for the Indian Lands Registry System (discussed in Section 5.1) and one on the use of the registry and its operational processes. The latter review has explored options for changing the registry's structure to enhance its value for economic development and economic analysis. These changes could include:

The evaluation of Indian Moneys, Estates and Treaty Annuities found that capital and revenue accounts are growing, demonstrating some success in the Band Moneys activity. Footnote 49 As discussed in Section 2.1, Band Moneys were not a significant focus of this evaluation and as such performance was not specifically examined. However, key informants noted that there are nonetheless continuing delays in providing access to these moneys, which First Nations argue presents a barrier to economic development. In particular, for capital accounts there are many approval stages for releasing funding to First Nations such as examination of financial audits. Case study participants in one community expressed concern over lengthy delays and noted that without timely access to money, economic development on the reserve slows down and band members have to borrow and cash-manage to make payments on leases.

Regional office participants also suggested that First Nations with significant capital revenue generation may prefer alternative moneys management options rather than the current structure under AANDC . This issue has arisen before and has resulted in a growing design and delivery alternative for the program. Under Section 64 (1)(k) of the Indian Act , the Minister is given the authority to release capital funds for use for any reason they deem to be in the benefit of the band. Current Band Moneys precedent is evolving in this area as a result of two court cases involving Samson and Ermineskin First Nations in Alberta. These two communities are being transferred direct control over their capital moneys under Section 64(1)(k) of the Indian Act . Footnote 50

Key informants noted that recently other First Nations have decided to pursue this option as well, which may yield favourable results and present a strong design and delivery alternative to the current Band Moneys structure. Key informants also noted that it may prove to be an easier alternative than the First Nations Oil and Gas and Moneys Management Act . They stated in particular that FNOGMMA has challenges around financial bonding requirements and community vote thresholds. Its statutory requirements oblige First Nations to develop financial codes, whereas they noted that the 64 (1)(k) option simply requires them to have a trust agreement with the chosen trustee. For future evaluation work, Capital trust accounts' performance under this alternative should be closely monitored.

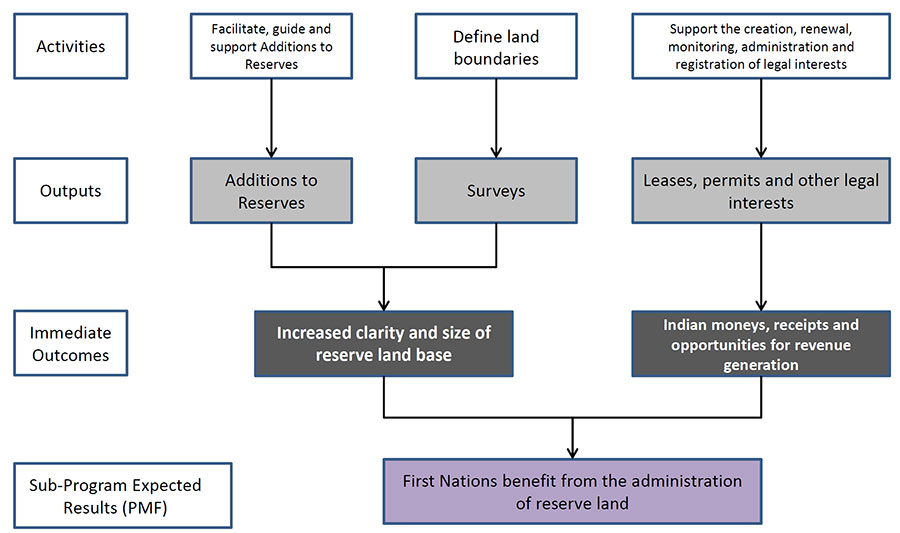

Additions to Reserve data demonstrate that the Treaty Land Entitlement model facilitates Additions to Reserve well: there were 197 Additions to Reserve (more than 350,000 acres of land) during the period covered by the evaluation, 120 of which were processed under the Treaty Land Entitlement category. Best practices under the Treaty Land Entitlement category of Addition to Reserve include pre-reserve designations of land to be added to reserve and ministerial rather than Order in Council approval.

Key informants, case study participants and document review all confirm that the TLE model expedites the ATR process. Footnote 51 This is corroborated by program data, which show that of the 197 ATR s processed during the evaluation period, 120 (61 percent) were TLE ATR s. The TLE model applies to the legal obligations category of ATR specifically under unique claims settlement legislation in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba: the Manitoba Claim Settlements Implementation Act and the Claim Settlements (Alberta and Saskatchewan) Implementation Act . ATR s processed under the TLE model are distinct in two ways:

First, communities are allowed to conduct votes on designations of the land before it is added to reserve. Footnote 52 Key informants note that the pre-reserve designation approach can facilitate the process because a common challenge for ATR s is the wariness of third parties regarding their interest in the land once it falls under the reserve framework, given the Indian Act 's unique rules and its leasing restrictions. These key informants suggest that having the land pre-designated for commercial or industrial interests, however, helps demonstrate to third parties that there is consent from the band for their activities to continue when the land is added to the reserve.

Second, the claims settlement legislation allows for an ATR to be approved via Ministerial Order rather than via an Order in Council, which is required in all other ATR cases. Footnote 53 Several key informants suggested that ministerial approval tends to be a quicker process than Order in Council approval as there is typically an extra stage of analysis applied by central agencies regarding the net benefit of the ATR . This is in contrast to legal obligation ATR s, which are not subject to this analysis given that they have already deemed to be a legal obligation.

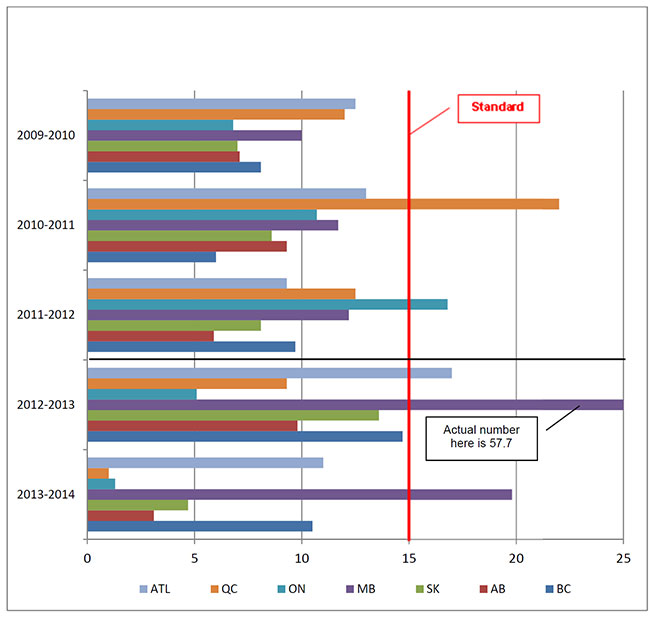

Case study key informants noted that the TLE model generally makes the ATR process faster, and this is corroborated by program administrative data. As Figure 3 demonstrates, significantly more TLE ATR s were processed than Order in Council ATR s:

Sixty-one percent of the ATR s approved during this period were completed by Ministerial Order. Moreover, Figure 3 indicates that Saskatchewan and Manitoba, where the special legislation applies, are the provinces that have had the highest volume of ATR s processed during the evaluation period. Saskatchewan had a total of 112 of the 197 ATR s approved during the evaluation period. In terms of total acres, Manitoba First Nations received the most: 147,981, representing 42 percent of the total land added to reserve. Footnote 54

One notable exception to the trend of most ATR s processed being TLE ATR s is that during the evaluation period, 34 non- TLE ATR s were completed in British Columbia. Of these, 19 were completed in 2013-14, following the establishment of the regional support centre. However, while this figure may at first appear to be a result of the support centre's influence, regional key informants note that the reason for a higher level of processing in that fiscal year is because First Nations placed additional emphasis on having ATR s completed, particularly those for specific claims; the regional office responded by devoting more time and effort to ATR files relative to other work. As such, data combined with key informant responses suggest that when additional resources are devoted to the process, non- TLE ATR s can also be expedited. Nonetheless, the overall data suggest that it is easier to have a TLE ATR processed using the same level of resources as a non- TLE ATR .

Thus, data, documents and key informants demonstrate that the TLE model has been very successful at expediting the Additions to Reserve process. The House of Commons report from 2014 suggested including key elements of the TLE model into future ATR policies or legislation. Footnote 55

Although the TLE model has been successful, challenges remain in the ATR process. Generally, there are several key steps in the ATR process Footnote 56 : the First Nation selects the land (which can be federal Crown, provincial Crown or private land), negotiations are undertaken with anyone who has a formal interest in the land, and then approval is requested from the Government (in principle from the Regional Director General and then from Headquarters and, finally, is subject to either ministerial or Governor in Council Footnote 57 processes). During the stakeholder negotiation portion of the process, First Nations often experience difficulty engaging third parties. The 2012 Senate report, for example, noted that municipalities and other third parties can sometimes be unwilling to negotiate in good faith. Footnote 58 In some cases, while the final decision rests with the federal government, a refusal on the part of municipalities and other third parties to negotiate can significantly stall the Additions to Reserve process. As discussed above, pre-reserve designations of land under the TLE model can ease third parties' concerns regarding their legal instruments by demonstrating the land in question can continue to be leased to outside parties following conversion to reserve status. Working to address third parties' concerns in this way can move the ATR process along more quickly. In other cases, easements are offered on specific portions of the land for these third party interests.

During other ATR processes, First Nations have found that third parties price land at higher than market value, knowing that the land is of significant value to First Nations given cultural attachment and/or economic potential; the 2012 Senate report on Additions to Reserve refers to this as "predatory pricing." Footnote 59

Other notable challenges include negotiating municipal service agreements. In cases where First Nations are gaining access to pre-existing services such as water distribution and garbage collection, they must negotiate agreements for continued service delivery. Ideally, municipalities always negotiate in good faith; however, witnesses to the Senate committee for its 2012 report on Additions to Reserve noted that sometimes negotiations are strained and delayed because municipalities do not want to see the Addition to Reserve processed. Footnote 60